By Anying Guo

WASHINGTON – In her first sociology class at American University, Ashley French found herself and her classmates participating in a privilege march game, veering into uncomfortable territory as the topic of race was brought up.

The game was supposed to act as an indicator of the variety of ways privilege can manifest itself in life, be it in an economic, social, or racial factor. For French, the game seemed to simplify these factors just to prove an academic point.

“[Our professor] wanted us to do this privilege march game, where you would step up into an inner circle if a situation applied to you,” said French in an interview. “The first half was about economics – like take a step forward if you could go to museums or movies growing up just to get us aware of that. She emphasized how she did not want to put people on the spot with a wide range of questions. But the next section was the racial privilege mark.”

French, born to a Vietnamese mother and white father, identifies as biracial. Many of race-centered questions were difficult for her to answer because of the unique racial space she exists in. When her professor asked questions such as “step forward if the majority of people at school were of the same racial background as you” or “if anybody on television resembled or represented you,” she chose to not step forward.

“For a good chunk of the questions, I didn’t move at all,” said French. “The point it got kind of weird is afterwards we had a kind of like group discussion and breakdown and people were talking.”

After the activity was over, French chose not to participate in the discussion about the race portion until her professor turned to her and asked: “Ashley, I noticed you didn’t move at all during the race march. Care to explain why?”

“She seemed to be coming at me as ‘you’re white, why didn’t you move [during the activity] to recognize that,” said French. “So I told her, I didn’t move because your questions were framed very singular race-wise. I’m biracial, so I’m not sure where that puts me in terms of your questions. She was definitely taken aback, because she wasn’t fully expecting me to say that type of thing for her, especially since she framed herself as this sociology professor who knows how society and race works. But the finer intricacies of race seemed a bit lost on her.”

The thought of reporting that incident and subsequent ones with her sociology professor didn’t ever occur to French, who didn’t consider what happened to her as instances of “outright racism, with a capital R.” Yet, she still thinks it would be helpful to know of any resources that may help other students who have dealt with situations such as hers.

Assistant Vice President of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion at American University Amanda Taylor, who views herself and colleague Dr. Fanta Aw as “conductors of the work” with racial discrimination on American University’s campus, knows full well how a sense of belonging plays into the student experience.

“There are variations in the sense of belonging in students of different racial backgrounds on campus and much of that is articulated in the classroom [where our work is focused],” Taylor said in an interview. “When you talk about how do you combat racism in the classroom, you need to make sure that every on campus becomes clearer about what that is, how it manifests, how our own perspectives and frameworks often allows us to see or not to see certain dimensions of that.”

Taylor has been working on diversity and inclusion efforts for years at American University, even before the creation of her current position in January of 2018. She stresses that what her role entails are not new ideas for the campus, but aid in the spread of mindset and intentionality within classrooms, especially in regards to racism against students, faculty or staff.

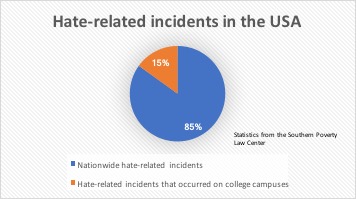

When asked about any training requirements for faculty, Taylor spoke about a required online bias training that emphasize the varying dynamics of a classroom setting. Training and workshops often vary from school to school at American University, but she emphasizes that they are occurring within each school. And with a rising number of hate crimes occurring on college campuses across the nation, the importance of these workshops are all the more necessary.

“I really think the scope of what we’re doing and the intentionality around it is new,” said Taylor. “The key part in doing the work is making sure we are actually communicating not just about what is being done but really listening to the community as well. It takes a lot of time.”

But there seems to be a distinct disconnect between what the administration is doing and what students know. Taylor admitted that students hav expressed to her their lack of knowledge about the new CARE network form, which was specifically designed for students (as well as faculty and staff) to anonymously file a report against another student, professor, or staff member, and the apparent lack of publicity regarding its release. In fact, many students according to American University Title IX officer Regina Curran, many students still think that racial discrimination falls under Title IX, which focuses on sex and gender-based discrimination.

“What isn’t clear to students is that Title IX has gotten so much attention given all the regulations and changing landscape around it,” said Curran. “People are viewing it as a catch-all for all discrimination when it was only supposed to narrowly be for sex or gender based discrimination.”

Yet, students like French and American University senior Sonikka Loganathan remain hesitant to report for a variety of reasons. Curran cites the power dynamic that tends to exist in instances of discrimination, especially between a student and professor, to be a factor in students turning away from speaking, much less speaking about their experiences with discrimination within the classroom.

Loganathan spoke extensively about the multiple instances of microaggressions she has faced in the classroom. One situation still stays with her today. Throughout the semester of the course, Loganathan’s professor consistently asked her questions about India and its history, even asking her to help hold and present a map of India during class, and mixing up the names of three Indian girls in the class.

“I didn’t report [those instances] because I didn’t think anything would happen,” said Loganathan in an interview, who considers what happened to her as the norm on campus. “I’ve heard so many horror stories [from other students] about professors asking how they could speak English so well. Reporting just doesn’t seem worth it.”

Both Loganathan and French both expressed frustration over the lack of transparency and accessibility from administration, with neither knowing about any sort of options to take when facing racism and discrimination within the classroom.

“When instances of racism or hate crimes happened, we got so many apology emails,” said French. “Those are nice, but wouldn’t resources be more important to include?”

Freshman Eric Brock, who is the co-chair for American University’s President’s Council on Diversity and Inclusion (known as PCDI), understands Loganathan and French’s frustrations. In an interview, Brock spoke about PCDI’s role on campus as a non-legally binding and open-minded resource that is comprised of students of different backgrounds and grade levels who are there to listen. Throughout this fall 2018 semester, the council has been listening to the concerns and perspectives of student organizations, even meeting with administration to fix those problems, which include discrimination in the classroom.

“With us, we are here for you,” said Brock, noting that despite his freshman status, he has heard and seen racist incidents occur on campus. “We say, this is what we can do to help, we can show you to another person and we can act in that way and at least address it.”

Despite his position as a student helping to breach the gap in communication between students and administration, he’s been frustrated by the vagueness his title entails. Brock is one of the 14 members on the council, picked out of 193 people. He emphasized how the diversity of the council has been beneficial to discussions, but not in finding any consensus for campus-wide problems.

“I’ve been frustrated with the fact that [PCDI council doesn’t] exactly know what we are supposed to be doing,” Brock said. “I know that next semester we’re going to start working on getting some bylaws and getting a process where we can recommend things to [American University President Sylvia Burwell] to add some structure. But right now, our main focus is listening to student organizations and making sure we just think about solutions.”

Brock also remains critical that the CARE network form should not be an end all, be all for students and faculty, citing the process behind the system still has elements of bias within it, the very antithesis of what the form is aiming to do.

“I don’t like the fact that some things aren’t being addressed [with the CARE form],” said Brock. “When the administration is in charge, there isn’t really due process. What happens is if there’s a faculty member that is the giver of the bias they can choose whether or not to pursue that, because that’s their colleague. So, there’s this implicit bias within the reporting system that reports bias. Isn’t that crazy?”

Taylor acknowledges that the rollout for the CARE network form hasn’t been ideal, but wants to reiterate the newness of the form and positions like hers and Brock’s. Expanding the amount of resources students, faculty, and staff alike can turn to in instances of discrimination remain a priority for administration; it’s just a matter of ensuring people know of that, says Taylor.

“[Administration] has to make sure everybody knows what to do with the information when they have it,” said Taylor. “Students should know that [what they say will] get taken seriously and responded to.”

Brock agrees, emphasizing how that he wants PCDI to be one of those resources. Both Brock and Taylor want to ensure that students feel comfortable telling someone, anyone, about their experiences with discrimination in the classroom, because it’s these situations that can make or break the student experience.

“There’s this fear students aren’t going to report it or come to us,” said Brock. “If more people knew about [PCDI] and there are students involved and they can come to real students, then that can be solved a little bit.”

“I told him I spoke German, but another kid said he was German but couldn’t speak it,” she said. The professor then made that student the “expert” on all things German within the class.

“I told him I spoke German, but another kid said he was German but couldn’t speak it,” she said. The professor then made that student the “expert” on all things German within the class.